For the last few years, I have used October to give myself a viewing assignment: a different horror film each day. Now that I have escaped the real life horror of New Zealand’s public service, I intend to write a piece inspired by each film.

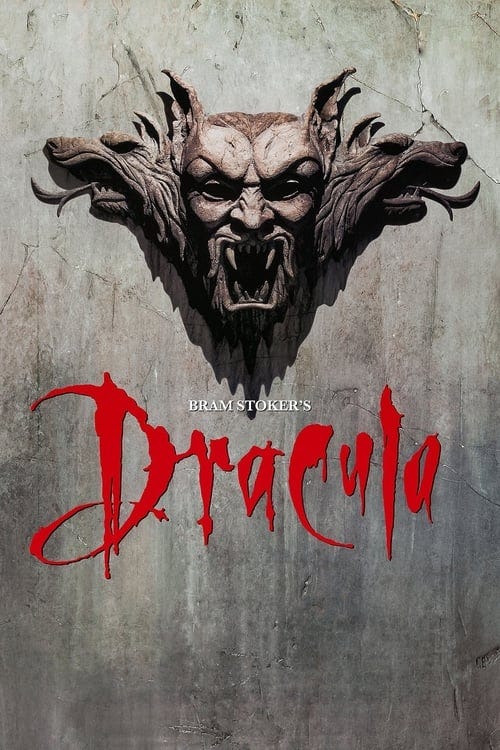

My fifteenth film is Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992).

Dracula has long been a bit of a blind-spot in my horror viewing (with the exception of his non-union German equivalent who is one of my guys). I tried to correct that last October by watching a bunch of films about the famous vampire. However, it was only today that I finally got around to one of the most beloved adaptations of Bram Stoker’s novel.

Given the current interest in Francis Ford Coppola, I decided it was a no-brainer to include his adaptation of Dracula in my viewing. I liked Megalopolis more than most people but I have to concede that most criticisms levied against it are valid. To me, the meta-narrative around that film renders a lot of those critisms moot. Its scale, its artifice, its folly are the point, and the earnestness of the love it communicates for his late wife Eleanor (RIP) makes it impossible for me to discount it entirely. I have professional respect for every wife guy from Shah Jahan to the director of five of the best films of the 1970s.

Of the films he’s made since this legendary run, his Dracula is probably the best-regarded. Like most adaptations of the book, this film follows the general narrative beats but hones in on a few particular areas of interest to Coppola. One of the most notable changes is the prologue which makes explicit the link between Dracula and Vlad the Impaler, the historic tyrant who defended Wallachia from the Ottoman Empire and likely inspired Stoker’s book. The only other adaptation I’ve seen to do this is the wonderful Drakula İstanbul'da, a Turkish film that paints Dracula as a brutal Crusader who hates garlic due to his Western palate and who can only be defeated with Islamic (rather than Christian) imagery.

Since the failure of One from the Heart in 1981, most of Coppola’s films have dealt with artifice in some way. Whether or not you liked the aesthetic of Cosmopolis, the intent behind it was clear. In Dracula, this artifice is achieved via bold, expressionistic choices like the super-imposition of shots upon one-another and the depiction of characters’ subjective reality objectively. The special effects were devised by Coppola’s son Roman who drew upon much older cinematic techniques. Although it neither looks, nor feels, like any earlier Dracula adaptation, it keeps one foot in cinema history, even setting some of its action in an early cinema. The remix of silent film imagery and techniques occasionally made me think of Guy Maddin (who has done his own Dracula adaptation).

The other reason this film has maintain its cult following is the cast, a who’s who of early 1990s figures. I loved the ensemble—even Keanu Reeves whose woodenness felt consistent with the film’s artifice. For me though, this film really centres on Gary Oldman whose aristocratic grossness makes him the most offputting iteration of the vampire (even less sexy than Nosferatu). Like many of Coppola’s films, this one deals with a transition from an old power structure to a new one. Morphing from one character design to another multiple times, Oldman’s Dracula combines elements of both the pre-Victorian (his backstory) and post-Victorian (his hyper-sexuality) worlds. His existence is an insult to both science and religion and he must be dealt with.

There’s a lot going on in this film and it wears a bit thin by the end of its 128 minute run-time but it is absolutely full of indelible horror imagery and you should really check it out if you’re (like me) late to the party.