Hari tau hau pākehā to all who celebrate!

I hope you and yours have got all the silliness of the silly season out of your system for another year and are ready for a dead-serious 2025.

Before I get in on the action with an obligatory ‘best of 2024’ list, I need to include a disclaimer. I feel like I say this every year but I have to emphasise that I’m at the mercy of New Zealand release dates (give or take an early screening or film festival). This means that some movies I have considered may have technically been from 2023 (for example, Priscilla, The Taste of Things and The Iron Claw were all in my top 50). It also means that a lot of major 2024 releases will have to wait until my 2025 list (I haven’t seen The Nickel Boys or Dahomey but am expecting to love both).

The other big asterisk is that the vertical integration of mainstream cinema has left several gaps where other modes of film-adjacent storytelling are emerging. Many of the most exciting young filmmakers originally made their names on YouTube and many of the best movies of the year are web videos. I have already praised The Phantom of Mar-a-Lago and Chime, a YouTube video and an NFT respectively. To allow for this, I haven’t adhered to any hard and fast rules about what a ‘film’ is (including length) and my list is more vibes-based. I know this may be difficult for purists but it’s been a free-for-all ever since the Europeans named a season of TV as the best ‘film’ of the 2010s.

So with that in mind, here are my favourite movies of 2024.

24. Blitz (dir. Steve McQueen)

Why I loved it: I think I’m the only person who genuinely loved Steve McQueen’s Blitz without any caveats or asterisks. It may be a relatively conventional tale of a child fighting to survive in wartime London but I’d argue that McQueen’s direction and historical perspective elevate it.

It’s a truism that western historical narratives have a tendency to elide the experiences of people of colour. The neoliberal solution to this is ‘colourblind casting’ where historical settings are populated with a diverse array of characters (think Hamilton or Bridgerton) that serve to obscure that actual racial tensions of the time. I was lucky to sit in on a presentation by Professor Anamik Saha from the University of Leeds who has been critical of this trend and it was never far from my mind as Blitz provided an excellent counterpoint.

McQueen is genuinely interested in Black British history (check out his Small Axe anthology), not just White history featuring Black actors. Here, he takes one of England’s proudest moments, its defeat of Nazism but focuses on the ways in which Britain may have not been as different from Nazi Germany as its most ardent propagandists would have you believe. Central to this is the challenges faced by protagonist George as a black kid in a racist country but I also appreciated the time spent with his mother Rita (Saoirse Ronan) as a woman and a worker in wartime London. Ronan received the most 2024 buzz for her role in The Outrun (where she played a woman outrunning a series of metaphors, each more obvious than the last) but she’s better here.

Why you should watch it: Maybe you missed out on the critical reevaluation of McQueen’s Widows and want to get in on the ground floor with this one.

How you can watch it: Blitz is available if you subscribe to Apple TV.

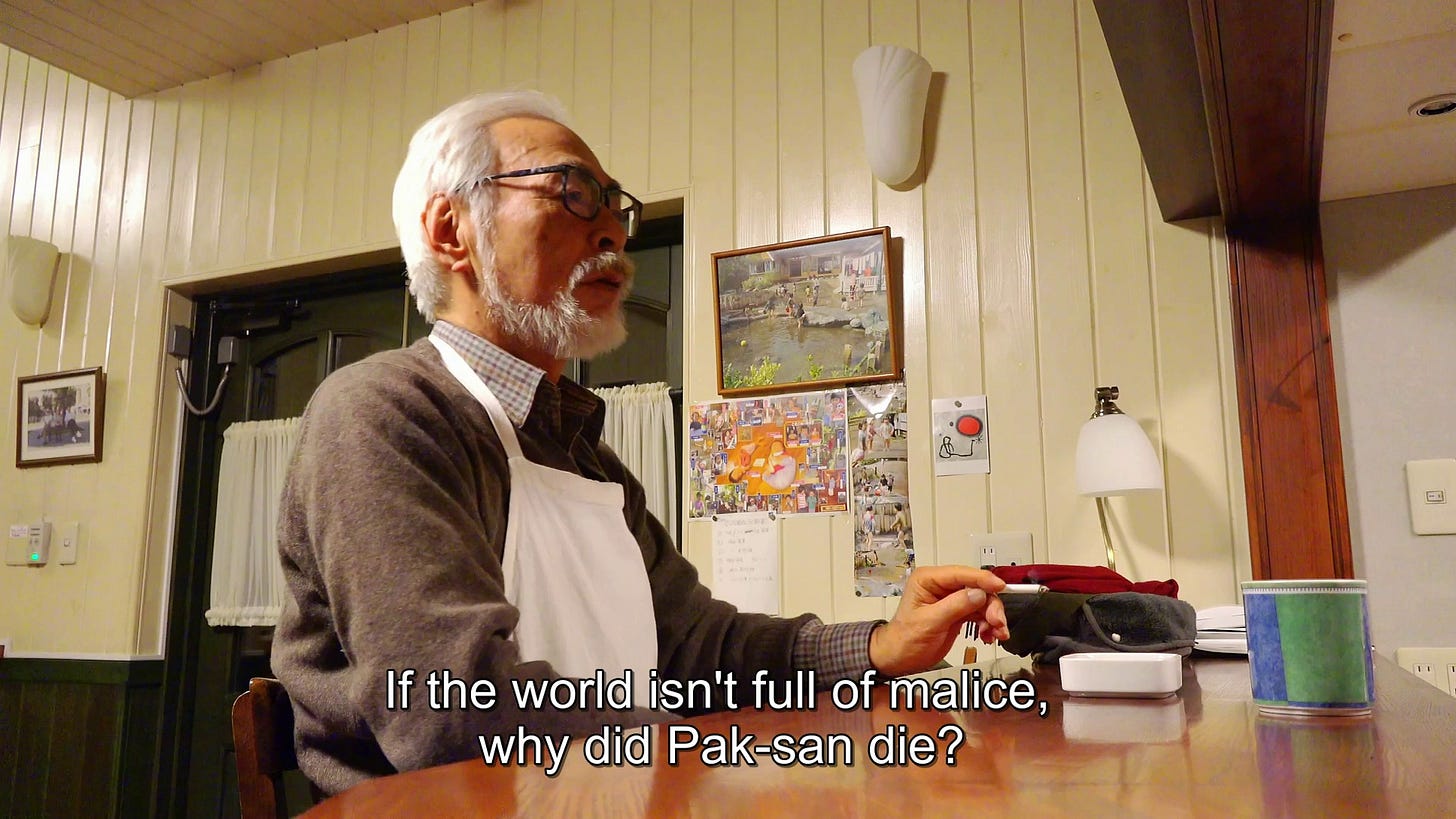

23. Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron (dir. Kaku Arakawa)

Why I loved it: I tend to be sceptical of ‘portrait of the artist’ documentaries. They are often highly-guarded pieces of propaganda showing whatever side of an artist that they want you to see (e.g. any documentary about Taylor Swift). Formally, they can leave viewers with the question: why not just engage with this artist’s work directly rather than engaging with it second-hand?

I loved Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron because it is both uncomfortably honest and an effective film in its own right. As in 2013’s The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness, the filmmakers were granted intimate access to central figures at Studio Ghibli that allow for serious candor. Spanning the seven years in which Hayao Miyazaki conceived of and directed 2023’s The Boy and the Heron, the film is about an old man looking back on his career as his old friends die one-by-one. The scope of the film includes the death of Isao Takahata in 2018 and its most devastating motif involves Miyazaki feeling as though he is being haunted by his old friend. Both Miyazaki and Takahata are among my favourite filmmakers of all time and the insight we are given into the more difficult aspects of their working relationship occassionally feel like something we shouldn’t be allowed to see.

As the film goes on, its subject becomes increasingly forgetful and unable to undertake the more finicky line-work of his art. As the old man worries that he’s losing his mojo, the film is edited with the confrontational abruptness of one’s life flashing before their eyes. Intercutting old interviews and clips from the director’s films, it allows viewers to access the brain of an artist whose process requires him to “lift the lid” on his mind.

Why you should watch it: You’re probably already a fan of Miyazaki’s work but this is still a powerful insight into the mind of an aging artist.

How you can watch it: Unfortunately there is not currently any way to watch Hayao Miyazaki and the Heron legally in Aotearoa.

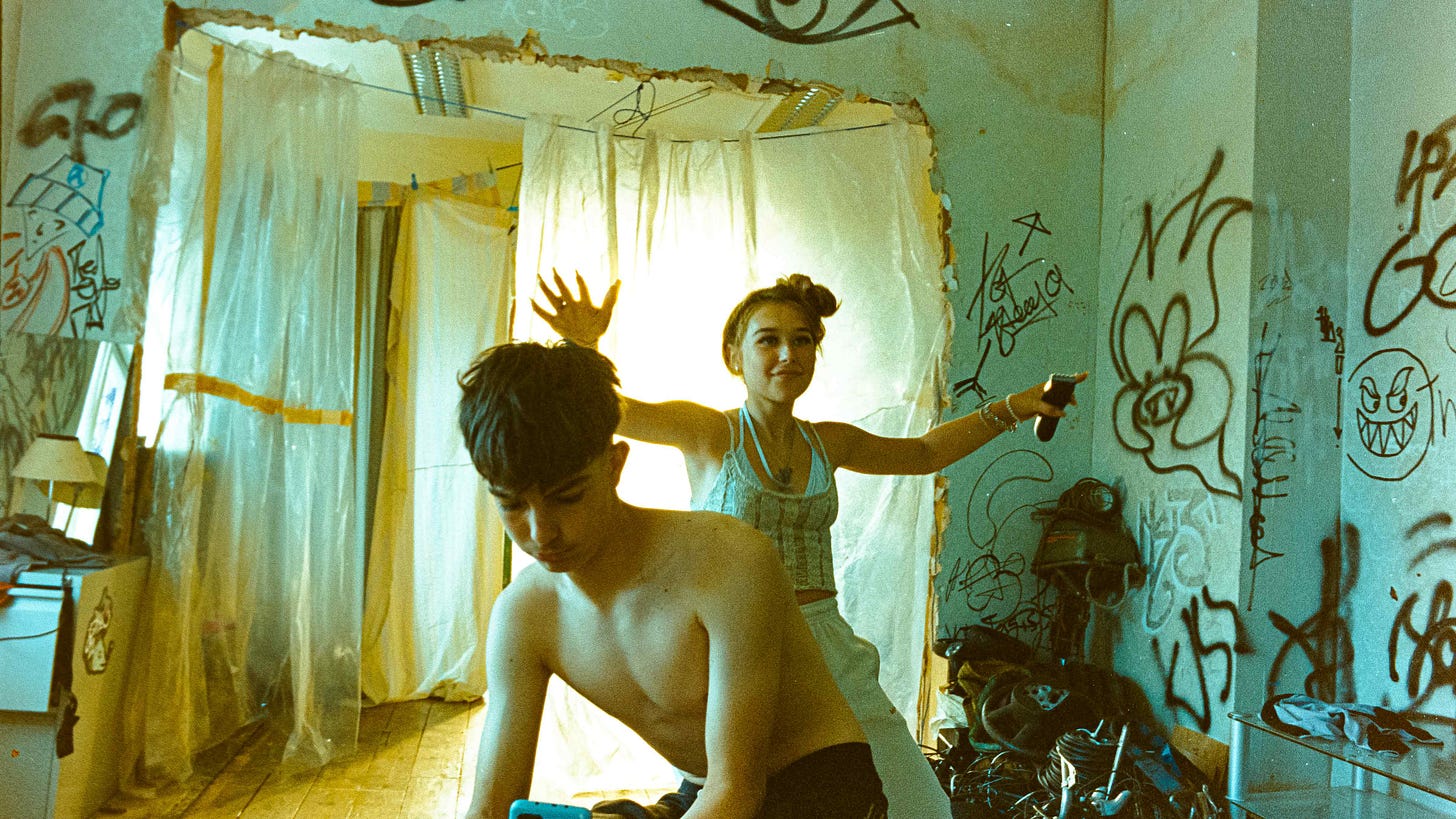

22. Anora (dir. Sean Baker)

Why I loved it: I have been a massive fan of Sean Baker since 2015. That year’s Tangerine and 2017’s The Florida Project are two of my favourite movies of the 2010s. Anora is Baker levelling-up, taking themes and techniques from his earlier work to create something with a greater budget and scope.

The last five movies Baker has directed have been about sex workers and I find the discourse around this element of his work can be a bit reductive, treating it as a curiosity in and of itself. For me, the depiction of sex work is most interesting for how Baker situates it within a broader economy of precarious labour (not enough people talk about the fact that most of these films also feature prominent scenes at fast food restaurants and diners). Anora is Sean Baker’s first film prominently featuring rich people, using their obscene wealth as a point of contrast. Although the film is its most fun during the antic romp through the city set-piece (reminiscent of Tangerine), its heart lies in the burgeoning sense of solidarity between Mikey Madison’s eponymous stripper and Yuriy Borisov’s hired goon.

The one thing the oligarchs fear is those whose labour is sex and those whose labour is violence realising their shared interests.

Why you should watch it: Come for all the excellent performances, stick around to see Baker’s other films.

How you can watch it: Anora is currently showing in cinemas around Aotearoa.

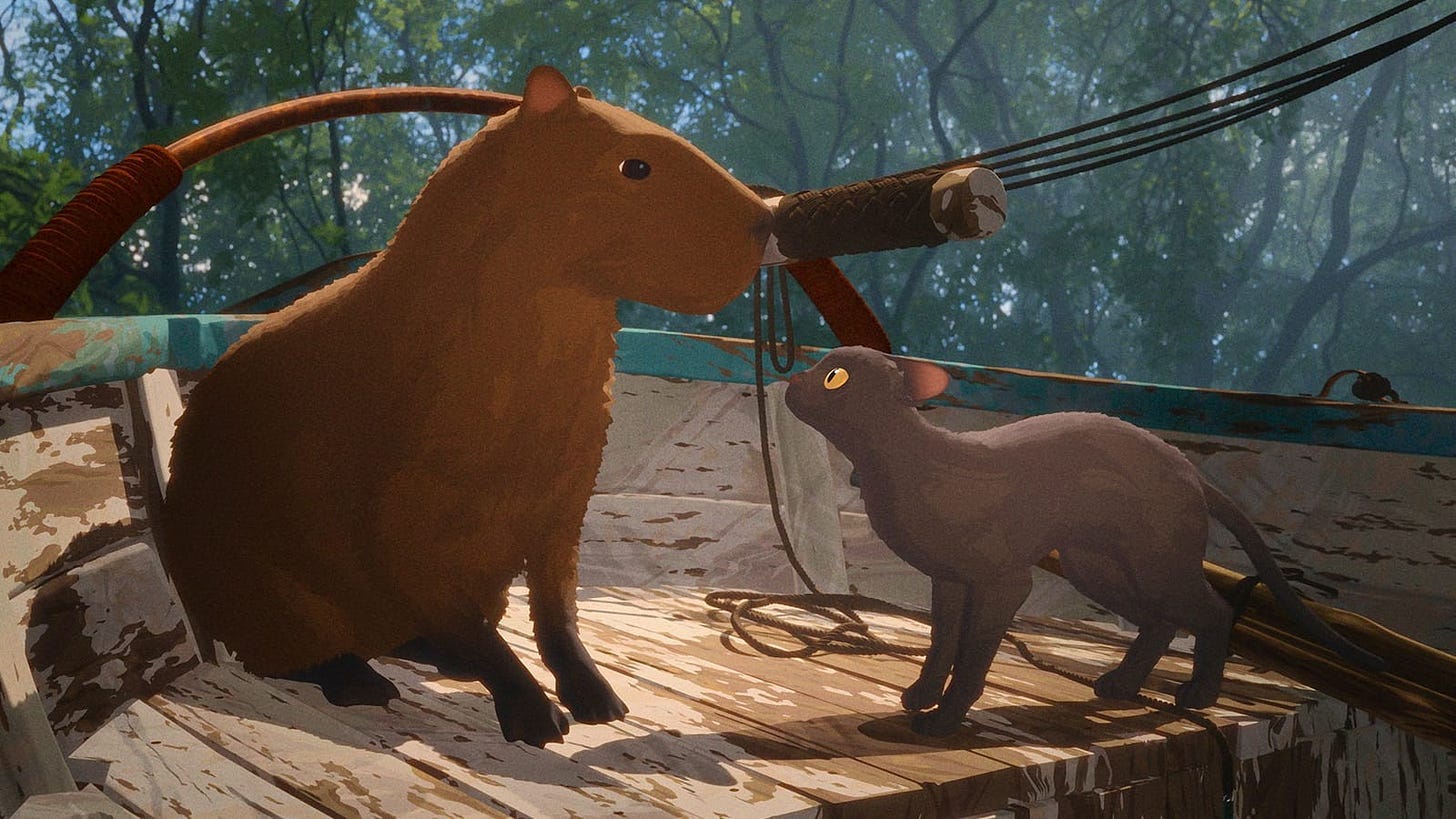

21. Flow (dir. Gints Zilbalodis)

Why I loved it: I avoided this film for the longest time after I heard Zilbalodis described as ‘the Baltic Miyazaki’. Every few years, Europeans will try to canonise one of their own as the next big thing in animation and they rarely live up to the hype (look at all the ugly cartoons that have come out of France in the last decade). When I started watching Flow, its animation initially reminding me of a graphics presentation in an earlier-model Windows computer but it quickly won me over.

The Latvian director is clearly working with a lower budget than his American counterparts, with very simple textures on each of his digitally-rendered animals. But they move like animals, they react to situations like animals and they sound like animals (the voice cast is entirely non-human). That’s not to say that this film is some sort of realistic modern Disney abomination; the situations the characters are put into are fantastical, apocalyptic, even biblical.

The film follows a small black cat (identical to Jiji from Kiki’s Delivery Service, maybe that’s where the Miyazaki comparisons come from) navigating a great flood that has wiped out humanity. In order to survive, Cat must find common cause with other animals, putting aside any differences. These ‘climate refugees’ are clearly viewed as ‘foreign’ by Cat: a capybara, lemurs, secretarybirds. Cat’s world has been turned upside down, going from predator of mice, birds and fish to having to share space with a giant mouse, giant birds and giant fish (conversely, lemur is sort of a tiny human). These are the same heady themes that Darren Aronofsky explored in Noah and Mother!: environmentalism, Old Testament morality, animal sentience, but with his thudding obviousness replaced with a light, graceful approach that even kids will grasp.

Why you should watch it: I watched this with a cinema full of very young kids and they were transfixed. Even if you can’t find anyone’s children to take to the movies, your reaction will likely be the same.

How you can watch it: Flow is currently showing in cinemas around Aotearoa.

20. Perfect Days (dir. Wim Wenders)

Why I loved it: Throughout a long and uneven filmography, Wim Wenders has often straddled the line between emotional honesty and contrivance. In this context, a film about a Tokyo toilet cleaner who finds meaning in life’s simple pleasures may sound insufferable. But, more than anything Wenders has made in decades, Perfect Days is elevated well above the sum of its parts.

For me, the thing that resonated most deeply is its depiction of inter-generational friendships. One of the greatest joys in the life of Hirayama (the absolute GOAT Koji Yakusho) is listening to cassettes of great musicians from the 1960s and 1970s like Lou Reed, Otis Redding and Nina Simone on his way to work. A less charitable filmmaker may have treated this as something that “kids these days” are incapable of understanding but here, it forms the basis of Hirayama’s friendship with the young Aya (Aoi Yamada). The relationship isn’t the most important one in the film but it is emblematic of Wenders’ optimistic point of view.

Screeds have been written about declining media literacy among Zoomers but it would be a mistake to interpret this as being due to anything inherently wrong with young people. It’s not their fault that they are served shit by media companies! The popularity of retro screenings and film societies among Generation-Z shows that this trend is driven by a lack of supply rather than a lack of demand. Maybe they just need a kindly figure like Hirayama to guide them.

Why you should watch it: To give yourself a sense of hope about the potential of human connection.

How you can watch it: Rent Perfect Days on AroVision.

19. Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World (dir. Radu Jude)

Why I loved it: If nothing else, 2024 was a great year for comedy. A good chunk of the films on this list are straight-up comedies and several others include scenes that had me hooting and hollering in the cinema.

In Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World, Angela (Ilinca Manolache) drives around Bucharest, interviewing people who have been injured at work to star in workplace safety videos (how many of these films are about people in unglamorous work?). In these videos, ‘raising awareness’ is secondary to letting employers off the hook for their role in the injuries. Romanian director Radu Jude punctuates the mundanity of this social realism with other forms of media.

Firstly, are Angela’s hilarious Tik Tok videos. The over-employed milennial has a side-hustle as an influencer who uses a filter to imitate Andrew Tate. She uses her platform to ironically(?) voice misogynist and racist opinions as a way to satirise(?) the manosphere.

Secondly, the film includes scenes from Angela Berge Mai Departe, a 1981 Romanian feminist film about a woman taxi driver. The viewer is invited to draw parallels between this optimistic depiction of women in the workplace and where 2020s Angela has ended up.

Finally, is an extended epilogue featuring the production of one of the videos. This scene comprises what is probably the most darkly funny shot of the year.

Why you should watch it: To remind yourself after watching Perfect Days that not all mundane jobs are equally valid.

How you can watch it: Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World is available if you subscribe to MUBI.

18. Sweet Dreams (dir. Ena Sendijarević)

Why I loved it: On the topic of post-colonial fiction, Australian poet Bobbi Sykes said:

Post colonial – fiction? ‘Post-colonial’ IS fiction. Have I missed something? … Have they gone? Fiction!!!!!

While official narratives of the 20th Century often involve European powers retreating from their territories in the global south, it’s clear that colonial power dynamics have endured in other ways.

In Sweet Dreams, the Dutch colonial administrators of an Indonesian sugar plantations are on the cusp of beginning that retreat at the start of the 20th Century. The death of patriarch Jan ignites a power struggle between his long-suffering wife Agathe, bumbling failson Cornelis, daughter-in-law Josefien, illegitimate son Karel and Indonesian mistress Siti. The colonial regime is crumbling, the decrepit European architecture looks like it’s about to be swallowed up by the jungle and the Dutch characters are mostly more comical than threatening. In particular, the heavily pregnant Josefien is not handling the tropical climate and spends the film sweaty, insect-bitten and uncomfortable.

In this context, Siti (the outstanding Hayati Azis) is able to exert a degree of power, even within the constraints of the racism and sexism imposed by the colony’s ostensible rulers. That the Dutch will have to give up their colonial possessions seems inevitable. The real tension lies in what kind of power structures will endure after they leave and what role Siti will play in them.

Why you should watch it: So many reasons! It looks stunning, it’s really funny and, as a piece of “post” colonial fiction, depicts a pivotal moment in modern Indonesian history.

How you can watch it: Unfortunately there is not currently any way to watch Sweet Dreams legally in Aotearoa.

17. The Bikeriders (dir. Jeff Nichols)

Why I loved it: I’m gonna be honest, I think a lot of you are sleeping on The Bikeriders.

In excellent queer reclamation of the seminal HBO gangster show ‘The Sopranos’ Belongs to the Gays Now, Chingy Nea argues that “every man and woman on The Sopranos is performing gender at such a high level that the show smacks of the stuff.” Watching Jeff Nichols’ new film, I couldn’t help but see the same performance of gender on display.

Criticisms of The Bikeriders have focused on the way that it feels derivative of other gangster films, especially Goodfellas. I would argue that this is a feature, not a bug. As alpha male Johnny, Tom Hardy is pure affect. Even within the text, his tough guy persona was crafted by copying Marlon Brando in The Wild One (one is left to draw conclusions about the English actor’s own technique). One can see the same kind of artificiality in the performances of Austin Butler, Michael Shannon and, especially, Jodie Comer. This is a photocopy of a photocopy, several levels of abstraction from the photo book on which it was based. It’s like a suburban dad was inspired by the book to buy a motorbike and took it out on weekends because that’s what he thought tough guys do.

Why you should watch it: To have fun watching some of cinema’s most beautiful boys playing dress-up and performing masculinity.

How you can watch it: The Bikeriders is available to rent across several streaming platforms in Aotearoa.

16. The Devil’s Bath (dirs. Veronika Franz, Severin Fiala)

Why I loved it: ‘Loved’ may be the wrong word but I was shaken to my core by this film about “suicide by proxy” in 18th Century Austria.

Franz and Fiala are known for making messed up Austrian movies (but I repeat myself) including Goodnight Mommy which I didn’t really care for. Like that film, there are some storytelling choices and camera techniques here that rely on arbitrarily withholding information from the audience and occassionally feel a bit cheap. Luckily this is a film where plot takes a backseat to a prolonged descent into despair.

The Devil’s Bath takes to its logical conclusion the tried and true formula of recent folk horrors like The VVitch and Hagazussa in which a woman is pushed to the edge in a historic setting. The bleakness of life at the time is horrific enough (even the weirder stuff here has a firm foundation in history) but the depression that it causes is as scary as anything depicted onscreen last year. This is a film where the physical violence (noting several trigger warnings for its gnarlier scenes) is less upsetting than the devastating emotional violence.

Why you should watch it: It is very hard for me to recommend this film to anyone in good conscience but you can probably work out whether it’s your type of thing.

How you can watch it: The Devil’s Bath is available if you subscribe to Shudder.

15. Evil Does Not Exist (dir. Ryusuke Hamaguchi)

Why I loved it: There was a very specific scene that made me fall in love with Hamaguchi’s most recent film. Two representatives from a real-estate developer undertake public consultation in a rural village because their employer wants to set up a glamping operation in their village (it’s part of a ploy to take advantage of COVID subsidies). The villagers grill the hapless city folks. Some are opposed to the project in its entirety. Others put forward good-faith questions about logistical and technical aspects of the project that the developer has clearly not considered. Anyone who has ever had to front public consultation on behalf of an organisation that doesn’t really care what the public thinks (e.g. a lot of government consultation with iwi) will relate to this scene.

But as great as this scene is (apologies to my fellow audience members for how hard I laughed), it’s a bit of a red herring. The film isn’t some simplistic snobs vs slobs, urban vs rural morality play. For one, the representatives are reasonably sympathetic, even if their employer isn’t. They may come into the village romanticising rural life but they’re genuinely eager to learn from the locals and Hamaguchi doesn’t shy away from the struggles and violence of what it means to live in close proximity to nature. This is a deeply ambiguous film, hard to pin down and uncomfortable with an eerie score by Eiko Ishibashi that may be my most replayed of the year.

Why you should watch it: As an opportunity to reflect on your own relationship with nature.

How you can watch it: Evil Does Not Exist is available to rent on the Apple TV Store.

14. The Convert (dir. Lee Tamahori)

Why I loved it: Lee Tamahori is back! My favourite New Zealand film of the year depicts an underseen chapter of our history with stronger filmmaking than the man has pulled off in years.

Why you should watch it: I know you’ll have already submitted on the Treaty Principles Bill but it’s worth reminding yourself that Te Tiriti emerged from an actual historical context in which pākehā had to be cognisant of their role of guests in Aotearoa.

How you can watch it: Rent The Convert on AroVision.

13. Gasoline Rainbow (dirs. Turner Ross, Bill Ross)

Why I loved it: In Gasoline Rainbow, five zoomers from small-town Oregon go on one last road trip together to Portland. Terrified of the world they’re about to graduate into, they spend the film reminiscing over a past that they are too young to have ever experienced. They listen to old music, talk about old films and develop friendships with older adults. Of course, they can’t hide from the future forever; the Oregon Trail stops dead at the Pacific.

I have been on the wavelength of the Ross Brothers since watching Bloody Nose, Empty Pockets in 2020. Their films are the definition of ‘vibes pieces’ (i.e. very much my shit), focusing on naturalistic, improvised interactions and striking imagery that keeps one foot in documentary, even when the music choices are too perfect to have been incidental. They always manage to feel authentically of the present even though most of what we do in the present is look back to the past.

Why you should watch it: As an innoculation against the ‘nostalgia for a time you never experienced’ trend in content like Stranger Things.

How you can watch it: Gasoline Rainbow is available if you subscribe to MUBI.

12. Rumours (dirs. Guy Maddin, Evan Johnson, Galen Johnson)

Why I loved it: People used to joke that the premise of every Pixar film could be summarised as “what if x had feelings?” (what if toys had feelings, what if fish had feelings, what if feelings had feelings, etc). The central joke of Rumours (maybe the funniest of 2024) is “what if world leaders had feelings?”

Here, each of the G7 leaders serves as an almost archetypal representation of a country, adhering to or deviating from stereotypes in very specific ways. None of them are one-to-one representations of world leaders but the closest is Guy Maddin-regular Roy Dupuis who plays the Prime Minister of Canada as a softboy male feminist struggling to deal with his marital issues. They are ostensibly meeting to draft a provisional statement in response to a crisis but get bogged down in trivial concerns, even as crisis comes to them.

Maddin is most famous for the way he uses silent film aesthetics in his work. The influence is less explicit but still important in Rumours. This is the rare contemporary film set largely at night where all the action is legible, largely through the use of highly-artificial sets, lighting and practical effects. The space they occupy bears as much relationship to reality as the bureacratic otherworlds in Pixar films and that’s part of what makes this film work so well.

Why you should watch it: If you love strong women (even if you love them too much) then this is the film for you.

How you can watch it: Unfortunately there is not currently any way to watch Rumours legally in Aotearoa.

11. Love Lies Bleeding (dir. Rose Glass)

Why I loved it: I think we’re increasingly seeing filmmakers pushing back on the recent trend towards sexlessness in cinema. Like Challengers (which I rate), Love Lies Bleeding is a crowd-pleasing genre film in which the characters’ horniness and sexuality are central.

Lou (Kristen Stewart) is a lonely woman in small town New Mexico who manages a gym in 1989. Jackie (Katy O’Brian) is a beautiful bodybuilder who arrives in town. The two get involved, first with one another and then with a criminal conspiracy involving Lou’s father (Ed Harris chewing the scenery). A strain is put on the relationship between Lou and Jackie by the latter’s determination to get bigger and bigger until the film verges on body horror.

Love Lies Bleeding was one of two 2024 films in which a pair of lesbians get in over their heads but while Drive Away Dolls was a ‘polite chuckle’, this is one of the year’s most visceral cinema experiences.

Why you should watch it: Fitspo.

How you can watch it: Rent Love Lies Bleeding on AroVision.

10. Kneecap (dir. Rich Peppiatt)

Why I loved it: Kneecap is the most propulsive movie of 2024. I can’t remember the last time I saw a music film that unfolded with this much breathless abandon.

If you haven’t heard of Kneecap, they’re a hip-hop trio from Belfast whose lyrics combine Indigenous language advocacy with playful references to sex, drugs and Irish Republicanism. The film fictionalises their origin story against the backdrop of Irish Language activism in the late 2010s. The result is one of my most fun cinema experiences of last year.

Once you’ve watched the film, you’ll immediately try and get tickets to see them live. Unfortunately their Meownui show is sold out. Please get in touch if you can hook me up with a ticket.

Why you should watch it: If your tastes fall anywhere in the venn diagram between hip-hop, political activism and lowbrow comedy, you’ll probably have a blast with this one.

How you can watch it: Rent Kneecap on AroVision.

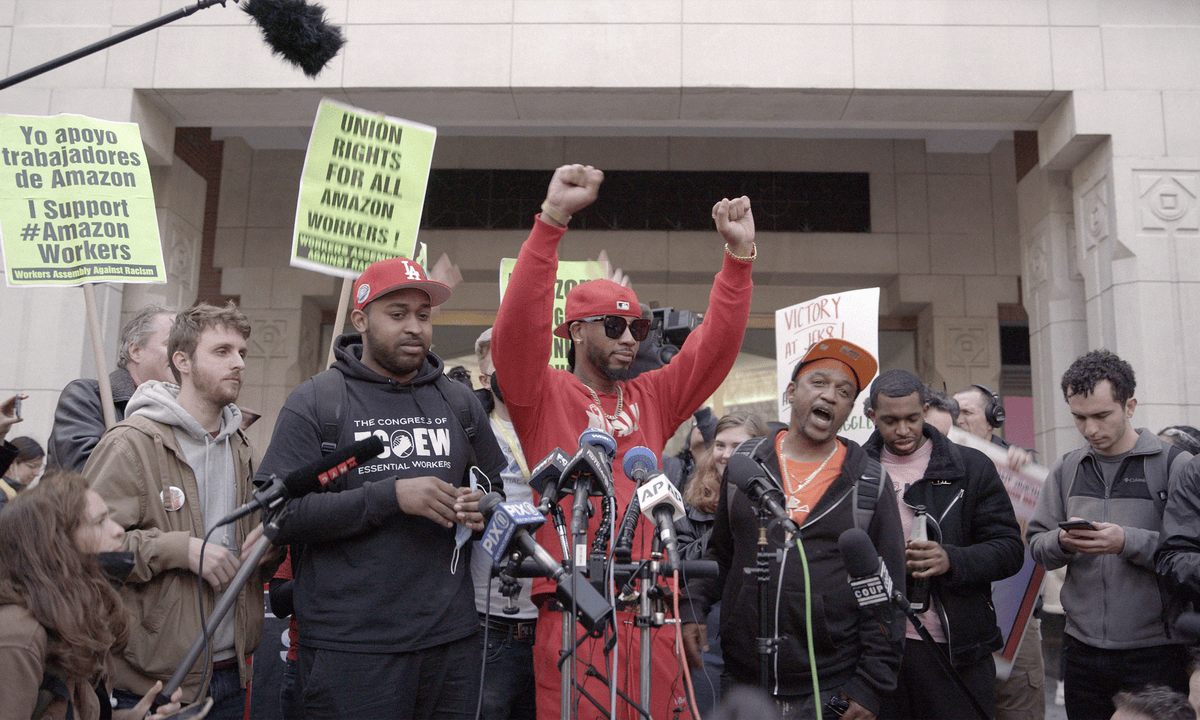

9. Union (dir. Julian Farino)

Why I loved it: I was lucky to watch Union as part of a Mayday event organised by UnionAID. Since then, it’s been really hard to see and its success has been largely hampered in a film industry in which Amazon is a major player.

This isn’t just a documentary just about Christian Smalls’ heroic efforts to unionise Amazon in Staten Island. It also acts as a procedural depiction of the nitty gritty of organising. It smartly doesn’t put Smalls on a pedestal but treats him as one player among many, never shying away from the knotty, uncomfortable, fraught dynamics involved in this kind of work. The long meetings and discussions may occasionally come across as a bit wonky but the film never lets you forget that these are real, normal people, many of whom you can probably relate to.

Why you should watch it: If you’re active in your union, you will find that a lot of this film rings true. If you’re not yet active in your union, it may inspire you to step up.

How you can watch it: Unfortunately there is not currently any way to watch Union legally in Aotearoa.

8. The Zone of Interest (dir. Jonathan Glazer)

Why I loved it: It’s been a year of discourse since this film came out and one key takeaway remains as true as ever: it is impossible to view this film and not think about the zone of interest that the United States and Israel have imposed on Gaza. This is something that director Jonathan Glazer has been unambiguous about and something I wrote about last year.

There is little left to say other than to share one of my favourite pieces of writing about it. In The Sentimentality of Evil, Sari Edelstein pushes back on the characterisation of the Höss family living next door to Auschwitz as an example of “the banality of evil”. In this context, the term becomes almost exculpatory when they are architects of the Holocaust, not simply helpless cogs in a machine. I think of all the comfortable bureaucrats in the United States, in New Zealand and elsewhere who are playing a role in actively immiserating people here and overseas while enjoying the fruits of bourgeois domesticity. I hope they, like Rudolf Höss are crushed under the historic weight of the violence for which they are responsible.

Why you should watch it: To remind yourself how those responsible for genocide behave.

How you can watch it: Rent The Zone of Interest on AroVision.

7. The People’s Joker (dir. Vera Drew)

Why I loved it: I know it’s a bit cheeky to include a 2022 film here, but there’s a reason that it took until 2024 to see Vera Drew’s queer punk masterpiece. Due to its unauthorised use of characters from DC Comics, this film has only recently been liberated from its legal purgatory. Luckily, this meta narrative has served to bolster Drew’s anti-establishment bona fides. There few supervillains she could face that are as dastardly as Warner Bros and the superhero industrial complex.

The People’s Joker is a miraculous lo-fi collage of queer superheroes, niche comedy references and genuine pathos. In a subculture as upwardly ambitious and deferential to power as the US comedy scene, it’s a breath of fresh air to see a film that refuses to pull any punches.

Why you should watch it: For some reason, NZIFF tried to market this towards the Armageddon Crowd but this film is going to land best with alt comedy nerds.

How you can watch it: The People’s Joker is available to rent across several streaming platforms in Aotearoa.

6. Soundtrack to a Coup d'État (dir. Johan Grimonprez)

Why I loved it: This is a dense documentary that covers a really complicated piece of history. It’s as if Adam Curtis made a film that replaced much of his voiceover with onscreen text. If you, like me, are a sucker for any film that cheekily edits together archival footage of pop culture and historical injustices, you’ll find this film worth the effort.

Soundtrack to a Coup d'État is ostensibly about the role that American jazz musicians played in the propaganda campaign that led to the assassination of Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba in 1961. But it’s also about the Cold War in general. And decolonisation. And the Civil Rights movement. Not to mention music. It includes a who’s who of towering figures of the time including musicians Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie and Nina Simone as well as political figures like Nikita Khrushchev, Malcom X and Fidel Castro. It may sound like there’s a lot going on in this film (and there is) but it goes down smoothly thanks Rik Chaubet’s dynamic editing and its jazz soundtrack. Even if you can’t always follow the intricacies of every historical event depicted or described, you’re sure to get lost in its rhythm.

Why you should watch it: The cooption of soft-power by hard-power is just as important now as it was in 1960. Think of all the celebrities who stopped talking about genocide once they’d endorsed Kamala Harris. There is no doubt that this is the kind of historical documentary that will make you think about the present.

How you can watch it: Unfortunately there is not currently any way to watch Soundtrack to a Coup d'État legally in Aotearoa.

5. Bird (dir. Andrea Arnold)

Why I loved it: As Andrea Arnold’s biggest fan, I am incapable of being objective about her films. When I introduced last year’s Film Society screening of Cow, I had multiple patrons coming up to me afterwards asking me why on earth I liked that film.

Bird, like most of Arnold’s films is about what it means to be a daughter. For 12 year old Bailey (Nykiya Adams), the adult she is closest to is her lovable loser of a father Bug (Barry Keoghan) but there are several adult figures who influence her coming-of-age. Bug’s new fiancé Kayley is an imposition to Bailey. Bailey’s mother Peyton is being gatekept by an abusive partner. Most intriguing is the titular Bird (Franz Rogowski), a fae-like figure who takes Bailey under his wing (get it?) and injects some magical realism into the mundane world.

I could talk for ages about how the British film industry is dominated by talentless poshos and Arnold has taken up Ken Loach’s mantle as the pre-eminent filmmaker interested in the working class. But for me, the appeal of Arnold is emotional rather than rational. There is something about the way she directs actors and non-actors and uses music that moves me to my core.

Why you should watch it: So Andrea Arnold can keep making films.

How you can watch it: Bird is getting a cinema release next month.

4. Rap World (dirs. Conner O'Malley, Danny Scharar)

Why I loved it: When I was a teenager, I ended up at the flat of a friend’s older brother after a party. Stopping periodically to hit the bong, this guy talked at us for what felt like an eternity about how the song Handlebars by Flobots helped facilitate his conversion to Buddhism.

Rap World stands above other millennial nostalgia for the way it evokes what it meant to be a small town white boy into hip hop in 2009.

Why you should watch it: To better understand your most embarrassing ex.

How you can watch it: Rap World is available for free on Connor O’Malley’s YouTube channel.

3. I Saw the TV Glow (dir. Jane Schoenbrun)

Why I loved it: There is now sufficient representation of millennial filmmakers in Hollywood that the nostalgia machine has been adjusted accordingly. Films like Rap World, Janet Planet, Y2K and Didi, are all aimed at people who are roughly my age. Of course, nostalgia can be a dangerous thing, and even when these films are at their best, it’s hard to escape the feeling that they’re good because they’re for me, because I share the filmmakers’ points of reference.

I Saw the TV Glow is much more ambivalent about nostalgia. For Owen and Maddy, their obsession with TV show The Pink Opaque in the late-90s endures as a monument in their sense of self, long after they’ve aged out of it. For Maddy in particular, its enduring prominence becomes unhealthy. If the show is more real than real life (and if real life is miserable) then why not retreat into fantasy? But Schoenbrun isn’t trying to throw the baby out with the bathwater and doesn’t shy away from the fact that the show may also play a key role in both characters coming to terms with their sexuality and gender identity. To what extent is our identity shaped by shitty children’s media and how do we retain any positive outcomes of that identification when confronted with the shortcomings of the work?

For me, The Pink Opaque is The Adventures of Pete & Pete, especially with the way real world musicians pop up. For others, it may be Buffy or Are You Afraid of the Dark? or Alex Mack. Your own specific point of reference matters less than the fact that by dramatising the painful links between past and present identity without didacticism or genre traps, Schoenbrun has made one of the best films of the year.

Why you should watch it: Because there is still time.

How you can watch it: Rent I Saw the TV Glow on AroVision.

2. All the documentaries about Palestine

Why I loved them: I know it’s a cop-out to put so many disparate documentaries and pieces of journalism together but given the quality and quantity of incredible work, there is a risk that this list could be dominated by films dealing with similar subject matter. In particular, I loved:

No Other Land (dirs. Basel Adra, Yuval Abraham, Rachel Szor, Hamdan Ballal)

The Last Sky (dir. Nicholas Hanna)

The Night Won’t End (dir. Kavitha Chekuru)

One Year in Gaza: Nowhere Safe (dir.

Where the Olive Trees Weep (dirs. Zaya Benazzo, Maurizio Benazzo)

Feature films are rarely able to be truly ‘timely’. Most of the others on this list have been in production for years. Themes may resonate well beyond a film’s release but they can rarely be ‘ripped from the headlines’. That’s typically not what film is for and journalism deserves to be considered on its own terms. But while a couple of years is a pretty standard length of time for a filmmaker, it is excruciating for someone forced to face-down the genocidal Israeli state. During 2024, we passed the one-year mark of the Israel ramping up its genocide of a captive Gazan population. This is a year in which babies have been born and murdered while many journalists and filmmakers have looked the other way. I want to recognise those who have documented the genocide, the occupation and the wider war on the Arab world.

I have watched as many documentaries about Palestine as I could this year and many of the 2024 releases pre-date 7 October 2023. But what has become increasingly apparent to me is that filmmaking as a means of ‘telling one’s story’ is more than a platitude when your story is so heavily censored. In the masterful No Other Land, we see Basel Adra learn to use a camera at a young age. The scene carries much greater weight than your typical ‘portrait of the artist’ and his proficiency with the camera needs to be understood as innately political. I was reminded of how Palestine has some of the highest-rates of English fluency in the Arab world, principally because so few native English speakers amplify Palestinian voices. Here, Adra’s adept use of the camera means that his documentation of the occupation of Masafer Yatta makes for one of the most harrowing pieces of filmmaking you will ever seen.

Masafer Yatta is just one site of an exterminationist political project that too few in power care about. Other sights have been covered in Al-Jazeera documentaries like The Night Won’t End and One Year in Gaza. I was also privileged to be able to host Lebanese-Australian filmmaker Nicholas Hannah for his documentary The Last Sky whose subjects are resisting Israeli imperialism from South Lebanon.

Why you should watch them: Because “listen to Palestinian voices” isn’t just a platitude; it is a moral imperative when they are being actively censored.

How you can watch them: Unfortunately there is not currently any way to watch No Other Land or Where the Olive Trees Weep legally in Aotearoa.

Nicholas Hanna has made The Last Sky available for free. Contact him for more information.

Al Jazeera has made its documentaries The Night Won’t End and One Year in Gaza: Nowhere Safe available to stream for free.

1. All We Imagine As Light (dir. Payal Kapadia)

Why I loved it: If you’ve read this far, you’ve probably noticed a few recurring themes that resonated with me in 2024. Characters who work thankless jobs. Labour organising. The cultivation of human connections, especially intergenerationally. All We Imagine As Light is my favourite film of 2024 because it dramatises all these themes with a tenderness and grace that I haven’t been able to shake since I saw it.

The main point of reference I’ve used to describe Payal Kapadia’s masterpiece is the films of my beloved Wong Kar-Wai. Like Wong before her, Kapadia identifies small moments of romance and connection in a massive impersonal city (in her case, Mumbai). But if I overstate that comparison, I risk undermining how singular this film is. The film is political but never didactic. Hopeful but never unrealistic. Quiet but with the best score of the year.

I can’t recommend it enough.

Why you should watch it: So we can have this film as a shared point of reference.

How you can watch it: All We Imagine As Light is currently showing in cinemas around Aotearoa.

What was I wrong about? What did I miss? Where can I get tickets to Kneecap? Get in touch to let me know!

Thanks for this. Going to be a useful reference for all the films I missed in 2024.