For the last few years, I have used October to give myself a viewing assignment: a different horror film each day. Now that I have escaped the real life horror of New Zealand’s public service, I intend to write a piece inspired by each film.

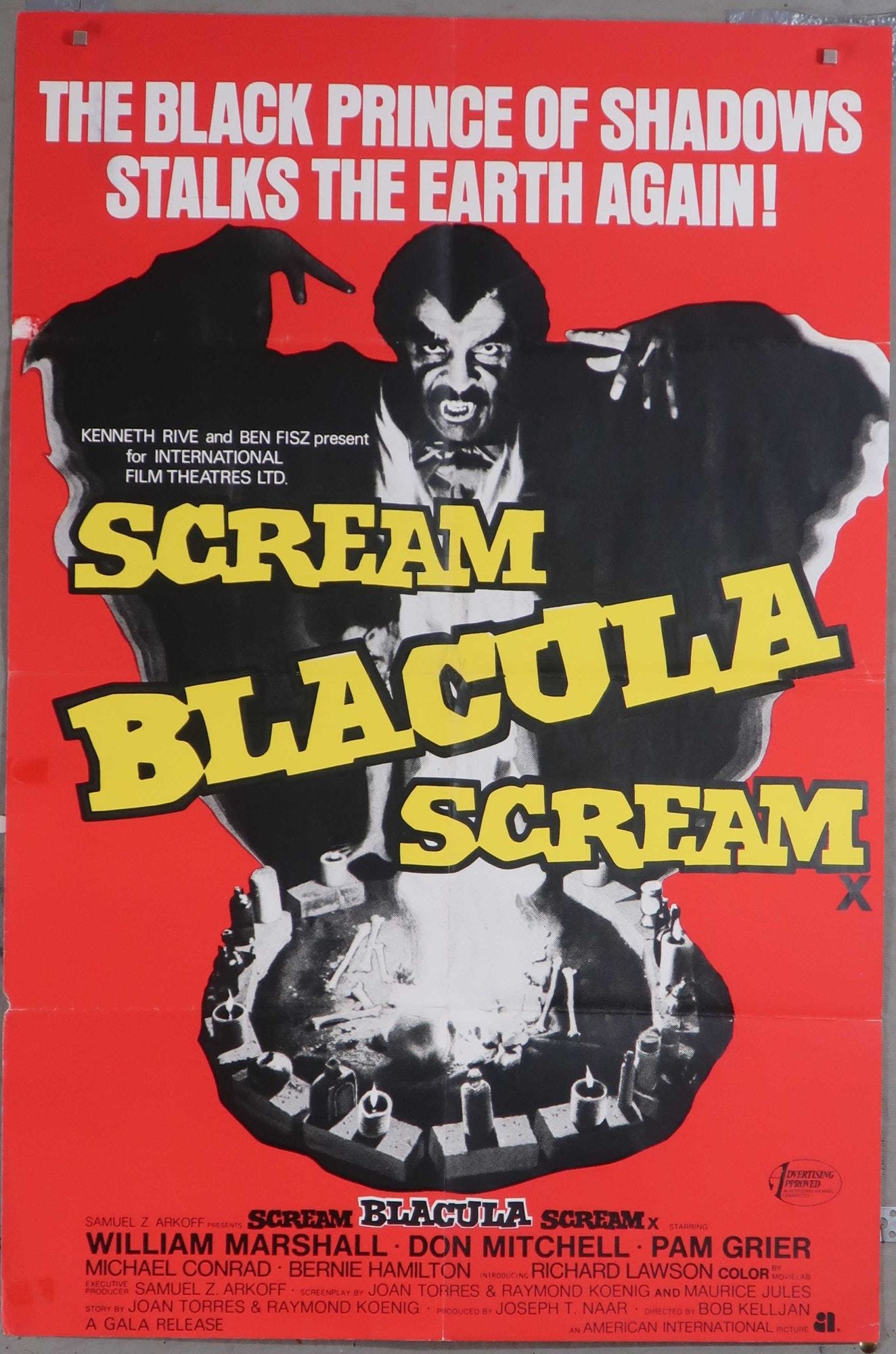

My nineteenth film is Bob Kelljan’s Scream Blacula Scream (1973).

When we last saw William H. Marshall’s Prince Mamuwalde at the end of 1972’s Blacula, he had taken his own life with sunlight, grief-stricken after the death of his beloved Tina. This may have seemed like the end of the road for Blacula but creatures of the night are a little like horror franchises: they don’t have a habit of staying dead.

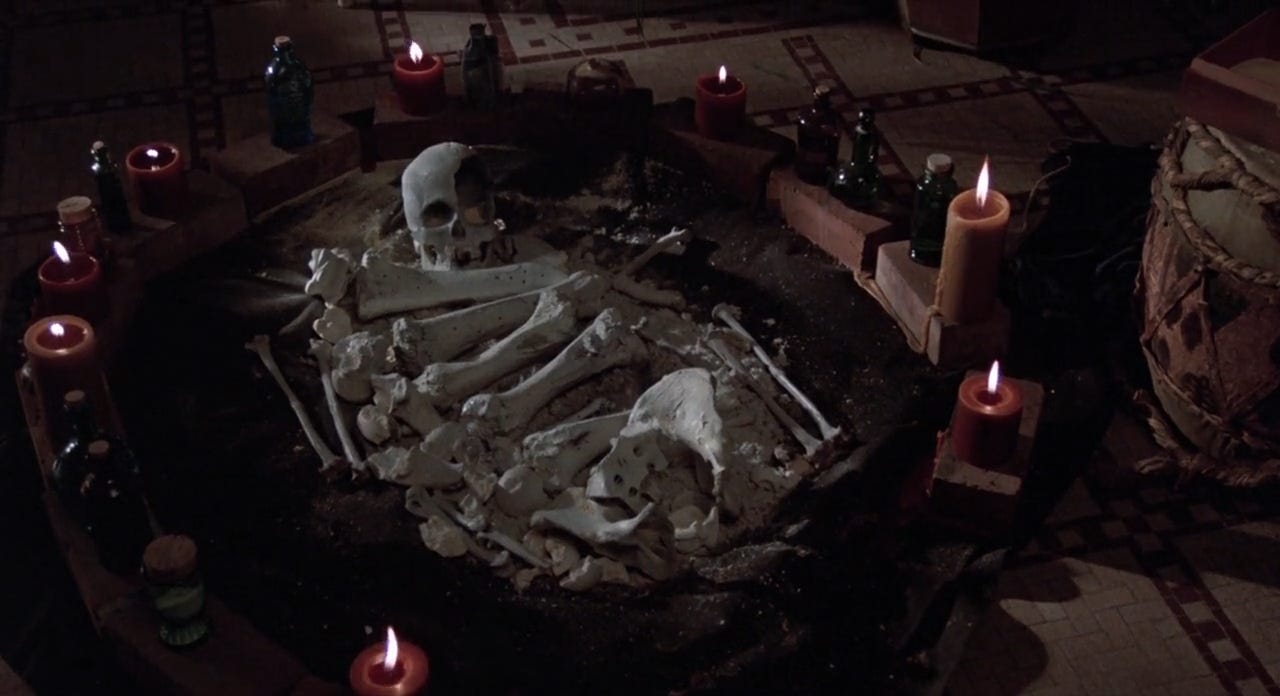

In this follow-up to the blaxploitation classic, Blacula is resurrected through the power of Voodoo by Willis (Richard Lawson). Willis is bitter about his Voodoo queen mother Mama Loa naming her apprentice Lisa (Pam Grier) as her successor over him. Finding himself in the middle of this succession crisis and recognising the incredible latent power in Lisa, Blacula sees a possible way out of his damned existence.

The addition of Voodoo into the lore of the highest-profile black horror franchise of the age makes perfect sense. Originally turned into a vampire by Count Dracula after the white aristocrat refused to suppress the slave trade, relationships of oppression and control are central to Mamuwalde’s backstory. Willis’ short-sighted actions excepted, the Voodoo practiced by Lisa is depicted as a force for good, a legitimate black religion that is misunderstood by racist cops.

If this black religion contains the potential for liberation, vampirism is depicted as a perpetuation of white racism, whether or not the proud Blacula admits it. At one stage, he sneers at a couple of pimps: “You've made a slave of your sister. You're still slaves, imitating your slave masters!” Given that Blacula has an army of vampires under his control, just as he was originally under Dracula’s control, this indicates a disappointing lack of self-awareness from the Black Prince of Shadows.

Reprising the title role, Marshall has a great screen presence. He’s already taller and has a deeper voice than anyone else onscreen but what makes him truly stand-out is his old-world mannerisms. Blacula talks like Christopher Lee and comes across as a complete outsider to the blaxploitation setting. When the fangs come out and he starts feeding, he’s genuinely terrifying. Then there’s Pam Grier, but nobody needs reminding how how incredible she is.

The film ends with a raid on Blacula’s mansion by cops wielding stakes. The image of these (mostly) white cops staking a bunch of black vampires is pretty confronting—a great example of the provocation that made films like this so controversial. This crudeness, combined with some spotty filmmaking decisions (especially the lighting) contributed to this film’s mixed reviews upon release but viewed through a modern lens, a lot of these decisions come across as pros rather than cons.