For the last few years, I have used October to give myself a viewing assignment: a different horror film each day. Now that I have escaped the real life horror of New Zealand’s public service, I intend to write a piece inspired by each film.

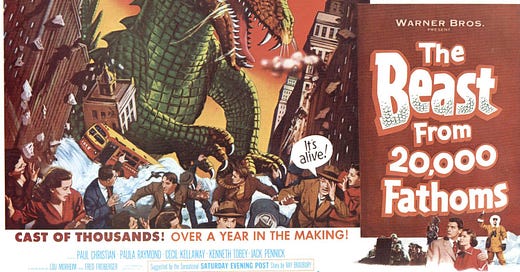

My twelfth film is Eugène Lourié’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953).

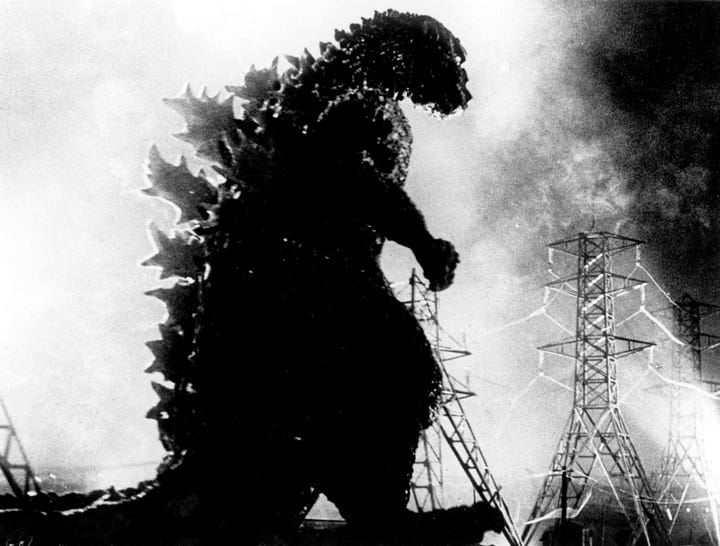

Of all the films of the 1950s, none comes close to 1954’s Godzilla in terms of the intensity with which it expresses the nuclear anxieties of the age. Watching that film, one is struck by how raw it must have been for Japanese viewers to be confonted such an explicit depiction of urban destruction less than a decade after the United States murdered hundreds of thousands of people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. There is something so uncompromising about that film that it can be surprising to realise that the Americans, the country with the most nukes, made a very similar one just a year earlier.

Tomoyuki Tanaka, Godzilla producer and one of the most important figures in the inception of the ‘kaiju’ (giant monster) genre, had not seen The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms when he started work on his own film but he was aware of it. Both are about giant prehistoric creatures who are reawakened by nuclear testing and must be stopped with science. Godzilla himself is almost a deity, inflicting nuclear destruction on Japan with his radioactive breath. The monster in this film is (slightly) more grounded, a rhedosaurus who had been trapped in arctic ice since the Mesozoic who brings both physical destruction and ancient pathogens.

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms adheres to quite a few conventions of the era. While The Incredible Shrinking Man super-imposed its opening credits against a cloud of radiation, this film has a vortex. For all its cynicism and paranoia, the film has trust and reverence for scientists and the scientific method, stemming from its grounding in hard sci-fi literature (this is an adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s The Fog Horn). If people, especially the military, would only listen to scientists then issues like this could be resolved. That’s not to say that this is really an anti-nuclear film like some American science fiction of the era (not to mention Godzilla) and none of the military characters are un-sympathetic. The rhedosaurus is awakened with radiation and put-down with radiation (thanks to an expert marksman played by Lee van Cleef). All that it asks for is that the balance of power to be weighted slightly more towards science.

The main thing that sets this film apart is the involvement of Ray Harryhausen, that legend of stop-motion animation. The monster looks stunning whether it is navigating a blizzard or eating cops in New York City. My favourite sequence involves an insert of nature footage in which a shark and an octopus face off against one another until the rhedosaurus intervenes. I’m probably a bit biaised in favour of the more tangible thrills of a man in a rubber suit playing a Japanese kaiju but the craft here is undeniable.

![The Terrible Claw Reviews: The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) [Friday Fakeosaurus February] The Terrible Claw Reviews: The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) [Friday Fakeosaurus February]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!lGyn!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1bd01b2c-270f-4f53-9433-8d6db62a174f_1500x1093.jpeg)