Note that this piece contains spoilers for the films discussed. In particular, Red Rooms, Longlegs, Trap and Strange Darling are reasonably spoil-able. If you’d rather not read this piece, then why not book a ticket to Justice for Palestine’s screening of Occupied on 1 December instead. This is the second screening I’ve had the pleasure of being involved in organising and I’m really excited for more people to see it!

Last month, as I was viewing as many horror films as possible in the manner of an ill-behaved American child gourging themselves on Halloween candy, I noticed a trend. A whole lot of recent films feature serial killers. This isn’t too interesting in and of itself; the recent obsession with true crime has been as well-documented as it is annoying and many of these films are in conversation with that trend. But what is interesting is the different directions in which these films take that conversation.

So as I formulate my thoughts on the year in film, I decided to begin with the roles that serial killers have played onscreen in 2024 (noting some of these films originally hit the festival circuit prior to 2024). I think these roles fall roughly into three camps:

1. The killer is my boyfriend

While most true crime obsession manifests itself as hyper-paranoid, antisocial, pro-cop psychosis, the equally unpleasant flipside of this is hybristophilia: when someone (usually a woman) is attracted to a serial killer (usually a man). Think of all the Netflix originals about sexy serial killers. There are two contradictory impulses at play (some people holding both at once): a conviction that an accused murderer is innocent and an attraction to someone because of their potential for evil.

I touched on hybristophilia a little bit in my 31 Days of Horror viewing for the role it played in Bertrand Bonello’s Coma. It is technically a 2022 film, but thanks to international distribution shenanigans, most people saw it for the first time this year alongside his much higher-profile The Beast. Dramatising France’s 2021 lockdown, Bonello made Coma to caution his daughter (and by extension young people in general) against “surrendering to the current mood”. One darkly comic example of this ‘mood’ is dramatised over a series of Zoom calls in which the protagonist argues with other teenage girls about which real-life serial killer is hottest. Here, hybristophilia represents giving into despair, literally falling in love with evil instead of working towards a better world.

Hybristophilia is most prominent in Pascal Plante’s Red Rooms. In this French-Canadian production, two women are contrasted against one another for their obsession with Chevalier, a man on trial for the murder of three girls and their broadcast on the dark web. Clémentine (Laurie Babin in one of my favourite performances of the year) represents the more benevolent side of serial killer fixation, wanting to see the good in Chevalier. She is taken under the wing of protagonist Kelly-Anne (Juliette Gariépy) whose interest in the case is much more ambiguous. There is something deeply sinister and internet-poisoned at the heart of Kelly-Anne’s motivation that is much more interesting than anything Chevalier could have done in those Red Rooms (which is mercifully never shown). Red Rooms would be one of my favourite films of the year were it not for an ending in which Kelly-Anne inexplicably decides to do the right-thing, undermining its thematic preoccupations.

Where some films seek to problematise true crime obsession, Woman of the Hour clumsily embraces it. Anna Kendrick demonstrates technical promise in her directorial debut and competently recreates the 1970s setting. Unfortunately, the point of view feels stuck in the 2010s. A genuine true crime film, this dramatises the story of so-called ‘Dating Game Killer’ Rodney Alcala who was able to charm his way onto TV mid-crime spree. Kendrick jumps through time, intercutting dramatisations of Alcala’s murders and his appearance on the The Dating Game in 1978. The intention is solid; Kendrick is trying to present Alcala’s murders as existing on the same spectrum as Hollywood misogyny (the depiction of police complicity in the murders is really effective here). But in order to achieve this, Kendrick centres herself, playing Sheryl Bradshaw, a struggling actor who just can’t seem to break through regardless of how many Hollywood sickos tell her how smart and hot she is. Although the real Bradshaw ‘won’ Alcala in the gameshow, she never ended up meeting him so the film has to invent an interaction between killer and would-be victim. The depiction of Hollywood sexism is about as nuanced as The Substance and the implication that this woman was able to escape because of how exceptional she was feels distasteful at best.

2. The killer is completely unremarkable

One way to undermine the presentation of a serial killer as an object of attraction is to portray him as just some guy. Think of the films of J-Horror maestro Kiyoshi Kurosawa where the psychology of the killer is completely besides-the-point when society itself is infused with an ambient violence. This theme is explored in his 1997 masterpiece Cure, 2016’s Creepy (another shoutout to an October horror piece) and this year’s excellent short film Chime (released as an NFT lol) in which the killer is barely embodied at all.

This was the intention of Oz Perkins (son of the GOAT onscreen psycho killer) in making Longlegs. Many have compared this film to Cure in the way its villain relies on a supernatural force to make other people kill on his behalf. Frustrated by true crime obsession and the romanticisation of serial killers, Perkins deliberately directed Nicolas Cage to play Longlegs as a washed up hair metal loser who just happened to make a deal with Satan. It’s hard to see anyone falling in love with his character (noting that even the blank slate of a killer in Red Rooms has groupies). I really liked this film, particularly the way that it demystifies the character, although Perkins’ intention of making the horrifying mundane sits awkwardly with all the Satanic panic stuff.

Unfortunately, this intention isn’t as successful in M. Night Shyamalan’s Trap. Josh Hartnett plays The Butcher, a serial killer who walks right into the cops’ trap: a giant pop concert with tens of thousands of attendees. He is able to keep slipping through their fingers because he is an empty vessel. Shyamalan has won back a bunch of fans in recent years, but even though I see myself someone with a high-tolerance for plot contrivances, I just can’t with his ridiculous movies. The Butcher is the most generic name for a generic killer with a laughably generic modus operandi. He is so unremarkable that he goes all the way back to being remarkable; being a blank slate becomes a superpower that enables him to evade capture. Hartnett is too good-looking and charismatic to sell the role and any time Shyamalan stumbles onto an compelling idea, he renders it irrelevant with a rug-pull.

3. The killer is a metatextual vehicle

Sometimes though, you just want to watch a film about a serial killer that has nothing to say about serial killers but just wants to have a bit of fun with the genre itself. The sheer volume of these films means that the figure is able to be presented completely disconnected from its real-life analogue, a horror archetype like a zombie or vampire.

In a Violent Nature is a revisionist slasher that extends the genre’s iconic ‘killer cam’ point of view shot to take up most of its runtime. I have heard critics compare this film to the likes of Terrence Malick and Gus Van Sant for its meditative stretches set in nature in which the wonderfully-named Johnny wanders. While I think those critics probably need to take a cold shower, there is something effective about how abstract this film gets at times. When Johnny stalks his hot young victims, their conversations are so generic and devoid of character that they land somewhere between AI, video game NPCs and characters in a CSI: Miami cold-open. When he kills them, the violence is at once completely over-the-top and clinical. This is the slasher taken to its logical conclusion.

If In a Violent Nature has a companion piece this year, it’s Strange Darling which shares its lovely daytime outdoor aesthetic (shot by Giovanni Ribisi of all people) and playfulness with audience expectations. Both films also notably end with lengthy sequences in which the ‘final girl’ is picked up by a passer-by with the film lingering on their car-ride like an extended cut of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. What’s unique about Strange Darling though is that the final girl is also the serial killer (I told you there’d be spoilers). This film has a too-cute narrative structure, opening mid-action in a way that immediately alerts the audience to the fact that information is being withheld. Even though I worked out ‘the twist’ immediately, there is still fun to be had in the way the film plays with audience sympathies and expectations around gender and genre. ‘The Electric Lady’ is such a hilariously evil villain (albeit one that we’re rooting for) that the film starts to play like a slasher Gone Girl. Contrivances aside, this still manages to be a rollercoaster of a film.

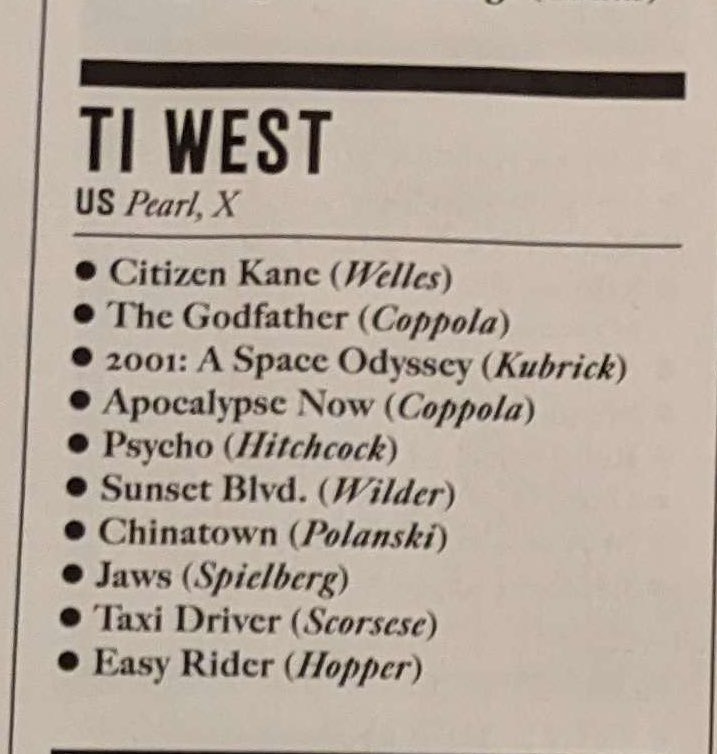

Finally, 2024 was also the year in which Ti West rounded out the trilogy that he humbly started during lockdown with X, a film notable for the excellent performances of Petone as Houston and Whanganui as rural Texas. Set in 1980s Los Angeles, MaXXXine regrettably doesn’t feature any Aotearoa landscapes. In fact, it doesn’t really do much at all. I adore Mia Goth in the role (especially in Pearl) but this is a film that replicates the texture of a bunch of better films as if that infers meaning in and of itself. Here, Hollywood is terrorised by The Night Stalker, a serial killer who sort of gestures at the decade’s reactionary backlash in the same way as Pearl sort of gestures at COVID via Spanish Influenza. West likes Psycho and Body Double? Good for him I guess but these references are still just references!

I’m not bold enough to draw any wild conclusions from this mini-trend other than “there sure are a lot of serial killer films coming out!” I could just as easily have written about all this year’s films about alien invasions, Satanic panics or body dysmorphia.

What I will say is that a serial killer is a symptom of a broken society. The only way an individual can get away with that scale of murder is if they experience some sort of protection from society (not to mention the murder that the state itself can get away with, within or outside its borders). That’s why real life serial killers are most likely to be men and/or white and/or cops and victims are most likely to be women and/or PoC and/or sex workers. Any narrative that frames these figures as somehow exceptional is trying to divert attention from the condictions that created them which is why phenomena like true crime and hybristophilia tend to be reactionary ones. I think most of these films are aware of that fact and are trying to respond directly to it or move beyond it. I just think some do it better than others.

![REVIEW] 'In a Violent Nature' Nails A Slasher's Perspective – Horror Press REVIEW] 'In a Violent Nature' Nails A Slasher's Perspective – Horror Press](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F11a75990-602a-46ae-89c4-c637f91aa2f1_1248x702.webp)